Algebraic patterns — Semigroup

Posted on July 14, 2016Introduction

An important concept in functional programming is that of composition, where an aggregate or complex element can be described as the assembly of smaller parts.

Not all forms of composition are the same however. Consider the two problems

- Assembling the pieces of a jigsaw-puzzle.

- Assemble a piece of IKEA furniture from its parts.

Putting puzzle pieces together and assembling furniture both involve composing smaller pieces into more complex, aggregate parts.

There is a difference between these two activities however, in that the assembly of furniture is highly linear and sequential. Generally it is necessary to start at the very first page of the manual, and following the instructions in order, from the first to the last.

Solving a puzzle is more freeform. Pieces from anywhere within it can be put together without enforcing any particlar order, like starting in the top left corner. This means solving a puzzle is easily parallelizable — simply enlist a friend to help solve a different part of the puzzle than yourself, and at any point combine the pieces from both efforts if possible.

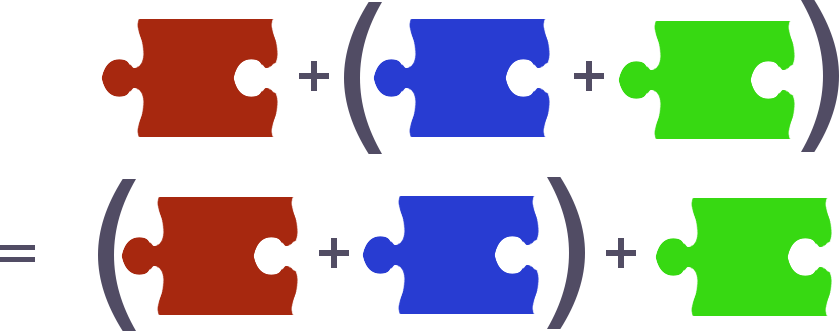

Can we algebraically describe the difference between these two problems? It turns out that it is easy to do so, by introducing a simple requirement on the method of composition. The key observation is that composition of puzzle pieces satisfy the following rule.

That is, given three puzzle pieces, these can be put together in two different ways, starting by combining the first and second, or staring with the second and third. Either way the final result is required to be the same.

A method of composition satisfying the above constraint is said to be associative. For a larger set of puzzle pieces the associativity law can be repeatedly applied, until it is possible to make the statement that a jigsaw can be assembled in any order.

Definition

A Semigroup is a data type together with a method of composition, ⊕, satisfying the associativity rule

a ⊕ (b ⊕ c) = (a ⊕ b) ⊕ c

Examples

Numbers with addition are Semigroups, as well as numbers with multiplication, maximum and minimum. Note that this means that as with Identity elements, the same datatype can have a given algebraic structure in multiple ways.

a + (b + c) = (a + b) + c

a * (b * c) = (a * b) * c

max(a, max(b, c)) = max(max(a, b), c)

min(a, min(b, c)) = min(min(a, b), c)

Strings with string-concatenation form a semigroup. We write ++ for

concatenation, so "foo" ++ "bar" is "foobar". Clearly it holds that

a ++ (b ++ c) = (a ++ b) ++ c

Similarly, lists or arrays, with list/array-concatenation are

semigroups. We write ++ also for this type of concatenation, so

[1, 2] ++ [3, 4, 5] is [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

The booleans are semigroups, with both || and &&

a && (b && c) = (a && b) && c

a || (b || c) = (a || b) || c

A very important associative operation is function composition. That

is, for a triple of functions f, g and h

f ∘ (g ∘ h) = (f ∘ g) ∘ h

Matrix multiplication is a binary operation that encodes the behaviour

of composition of linear functions, and is thus also associative,

making the set of n-by-n matrices a semigroup for any n.

A frequency map is a map from values to “frequencies”, which are

numbers intuitively representing the number of times a particular

value has been “counted”. This is a natural way of modelling e.g. the

outcome of an election. In an election with candidates A, B, C

and D, the results of counting the votes can be represented as a

frequency map.

{ A: 2, B: 4, C: 3, D: 1 }

The composition operation simply adds frequencies.

addFrequencies({ A: 2, B: 1, C: 3 }, { B: 3, C: 1, D: 5 })

>> { A: 2, B: 4, C: 4, D: 5 }

This operation is associative for all values. Notice that calculating

the results of an election is a typical example of a parallelizable

problem. No single person counts each vote in a large election, but

rather results are aggregated first by district, the summarized into

complete results. The fact that this is possible to do is neatly

described algebraically by the associativity of the addFrequencies

operation.

Comparators are semigroups. A comparator is a function from two

values to the set { LESS, EQUAL, GREATER }. In Java and many other

languages LESS is represented by any number < 0, EQUAL by 0 and

GREATER by any number > 0, so that one can write

function compareNumbers(i, j) {

return i - j;

}

The result of composing two comparators is a new comparator that

compares by its parts in right-biased-order. For instance

firstNameComparator ⊕ lastNameComparator is a comparator that

compares first by lastName then by firstName.

function composeComparators(c, d) {

return (x, y) => {

const comparisonResult = d(x, y);

if (comparisonResult === EQUAL) {

return c(x, y);

}

return comparisonResult;

};

}

As an exercise, check that comparator-composition is associative to verify that comparators for a semigroup.

A “weird” associative operation is ⨮, which is defined as

x ⨮ y = y

that is, it takes two arguments and discards the first. Any type is a semigroup paired with this operation.

Similary one can define ⨭ as the operation that discards its second

argument, also forming the composition of a semigroup.

Pairs of elements that are semigroups are semigroups with composition

defined component-wise. For example (4, "foo") ⊕ (7, "bar") = (11, "foobar") where we use the + semigroup on numbers and ++ on

strings.

Applications

The associativity condition is a suitable design goal in many

situations, for the reason that it encodes the notion that the order

of taking operations is irrelevant. Note that this is different from

saying that the order of elements is important. For instance the

expression "foo" ++ "bar" is not the same as "bar" ++ "foo".

Complex behaviour described through associative composition is simpler and easier to understand, since the order of operations is not important.

A notable example in the javascript world that fails the

associativity condition is the .pipe method in the gulp build

system.

The form of parallelism induced by the associativity of the semigroup operation is heavily relied upon in the Map-Reduce programming model. We’ll expound on this in more detail in a later article, as this is more easily developed algebraically after defining the concept of a Monoid.